The Commercial Space Station Revolution

The ISS is amazing: it's the largest object ever built in space, and the most expensive single object on Earth. It's brought us many revolutionary discoveries and inventions. However, human spaceflight has stalled in low Earth orbit, despite having gone to the Moon 50 years ago. It has been the only destination, despite the dreams of many to travel the heavens. But as the space station nears the end of its life, NASA is opening it up to private enterprises, hoping that the civilian market will make good use of it rather than all that effort going to waste.

One of the biggest hurdles to private involvement in the ISS has been research law. All discoveries and inventions on the ISS are public property - nothing can be patented, so there's little incentive for tech companies to conduct wildly expensive R&D on the ISS without reaping the profits. While NASA is loosening those restrictions in recent times, it's still a public platform. This is important, because without an economic incentive for private companies to go to space, traffic volume will stay low and space travel will stay pricey. Six astronauts working full-time for two decades have discovered a lot, but not nearly as much as dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of private sector scientists and engineers working on many projects in competition with one another would be capable of.

However, many companies are looking to build private space stations and rent them out for others to use as they see fit, whether for researching new pharmaceuticals, food production or manufacturing techniques, or anything else that can be marketed. There are few examples of private research, for the above-mentioned reasons, with possible exceptions being product tests like the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module that proved the worth of Bigelow's whole product line. The BEAM is currently cleared to remain on the station until 2028, so it's basically a core module now. One example is Made in Space, which already tested its manufacturing technology on the ISS in early 2018, and plans to produce flawless ZBLAN optical fibers in space that are impossible to create on Earth.

Bigelow BEAM, the first private module on the ISS, proving the concept (source)

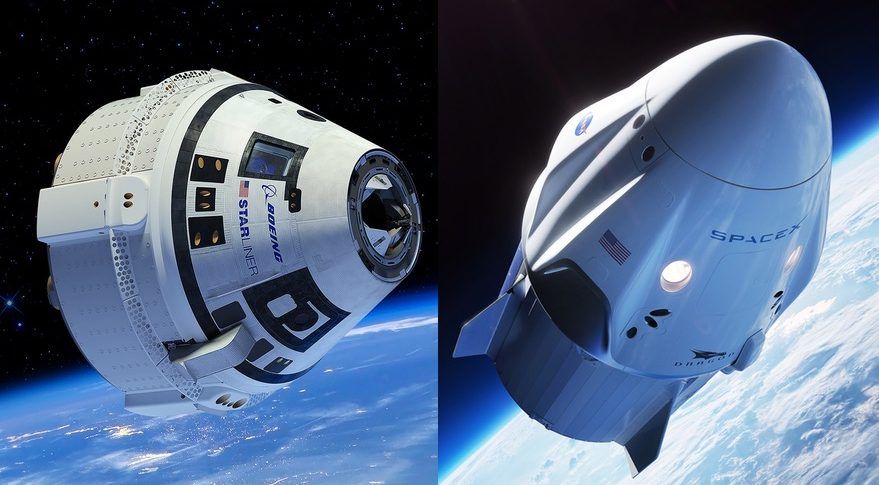

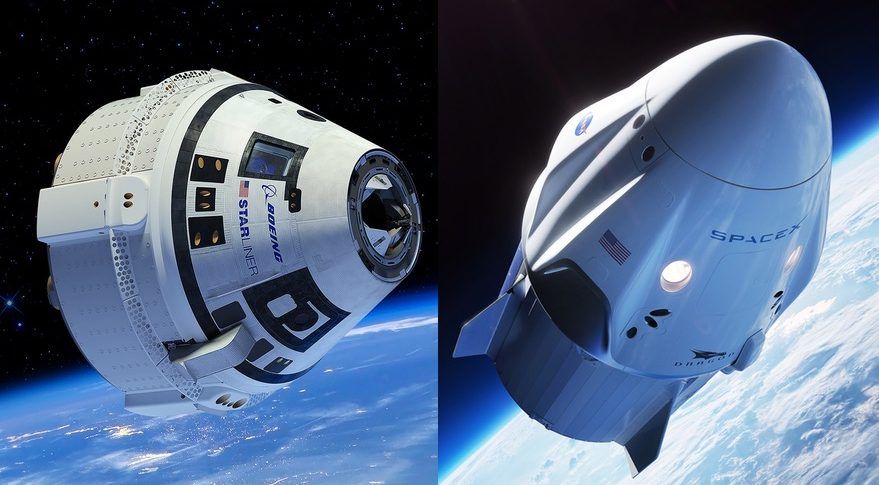

The other biggest hurdle to private industrial and research activities in orbit is the cost of launch vehicles. This barrier is rapidly being demolished by SpaceX and Rocket Lab, soon to be joined by Blue Origin and others. Spaceflight and space industry is becoming economically viable. Additionally, much of the infrastructure necessary for continuous industry in low Earth orbit is already in place. Thanks to the Commercial Resupply Services program, a whole series of private launchers and cargo spacecraft have been developed for the ISS that could easily service commercial space stations as well. As reusable spacecraft such as the SpaceX Dragon and Sierra Nevada Dream Chaser prove their worth and fly lots of missions, the costs will continue to come down, spurring more economic development in Earth orbit. Alongside this, NASA's Commercial Crew Development program has also developed the SpaceX Crew Dragon and Boeing Starliner, which while unable to service the upcoming Lunar Gateway, will be very capable of carrying passengers and workers to Earth-orbiting space stations. As both are reusable, their prices should also come down as they compete for paying passengers in a growing market.

Boeing Starliner and SpaceX Crew Dragon, both products of the Commercial Crew Program (source)

So, who's going to build the first private space stations? MirCorp, which temporarily took over the Mir space station in 1999, set a strange precedent. Mir was set to deorbit in anticipation of the International Space Station, but MirCorp offered to buy it and use it for commercial activities such as space tourism, the first orbital film studio, and private research. They even flew the first paying space tourist, Dennis Tito, and commissioned the first privately funded crew and resupply missions. However, NASA viewed it as a political threat to the ISS (other partners were thinking of backing out), and forced Russia to shut it down.

A few years later, Bigelow Aerospace was born, armed with the leftover patent of NASA's TransHab expandable space station module. They've been developing it for years with intent to build multiple space hotels and space labs, and boast far better performance than the hard cans that compose the ISS, and really every space station up to this point. As shown above, the BEAM on the ISS has proven these claims to be true. Perhaps the biggest thing holding back Bigelow has been both demand as well as launch costs, but both obstacles may be going away.

Bigelow Commercial Space Station aka Alpha Station, composed of two B330s (source)

The B330 is the main product Bigelow offers, being a 330 m³ expandable habitat that has more habitable volume than one third of the ISS at a fraction of the mass and complexity. These can be outfitted as habitats, labs, manufacturing facilities, storage, or anything else the customer dreams up, and allow them to entertain tourists, do research, or manufacture rare products to export back down to Earth. As you can see in the picture above, it could easily be served by Dragons or Starliners, which are just as technologically mature and ready to go as the B330 modules that have been developed over the last decade. Launch services for it are already contracted with ULA, and it's just waiting on a tenant to sign up.

Possible tenants include Made In Space and NanoRacks. Made In Space, as previously mentioned, has mature technology for producing high-quality optical fibers, and is currently developing the Archinaut, a revolutionary 3D printer that goes on the end of a robotic arm like the one that assembled the ISS. This has the potential to make massive objects in space, unlimited by the constraints of an assembly area like traditional 3D printers. They're also working on recycling old space station parts as more material for the Archinaut.

NanoRacks Ixion module, a spent upper stage refurbished as a space station module (source)

This ties in well with NanoRacks' ambitions to use spent upper stages as space station modules. This has been done before, with Skylab being a Saturn V third stage reworked into the first US space laboratory; but while Skylab was specifically designed for that purpose, NanoRacks wants to develop cutting tools to rework any spent upper stage into a usable hab. The big advantage is that its already built to withstand the vacuum of space, and it's much cheaper to launch into orbit - especially if it already delivered a satellite or station module. This has the added benefit of cutting down on space junk, and could be used to fuel the Archinaut. Together, NanoRacks and Made in Space are cutting down on the barriers to a space economy.

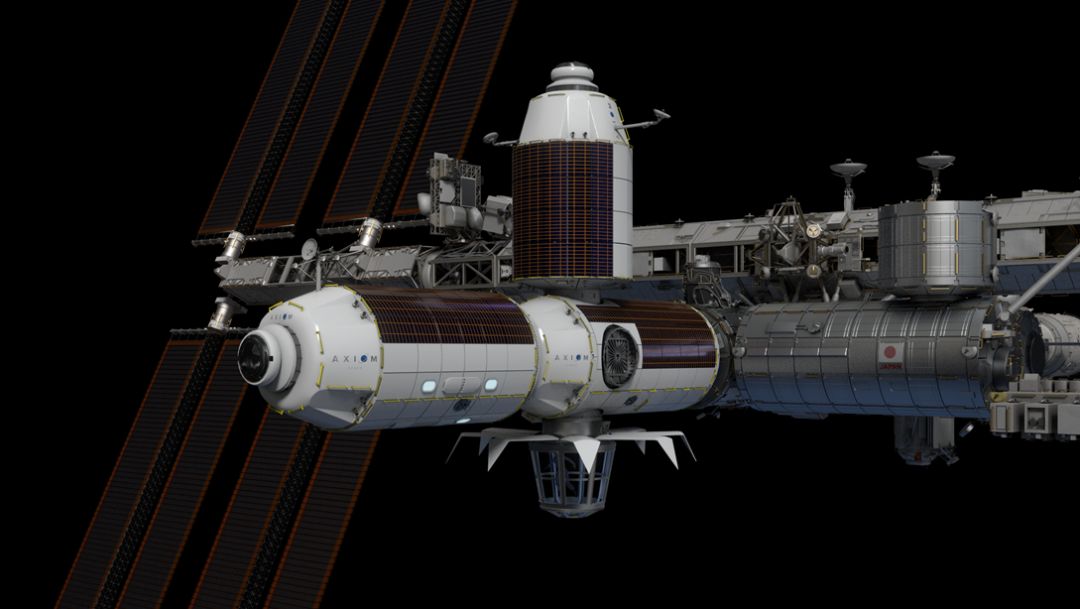

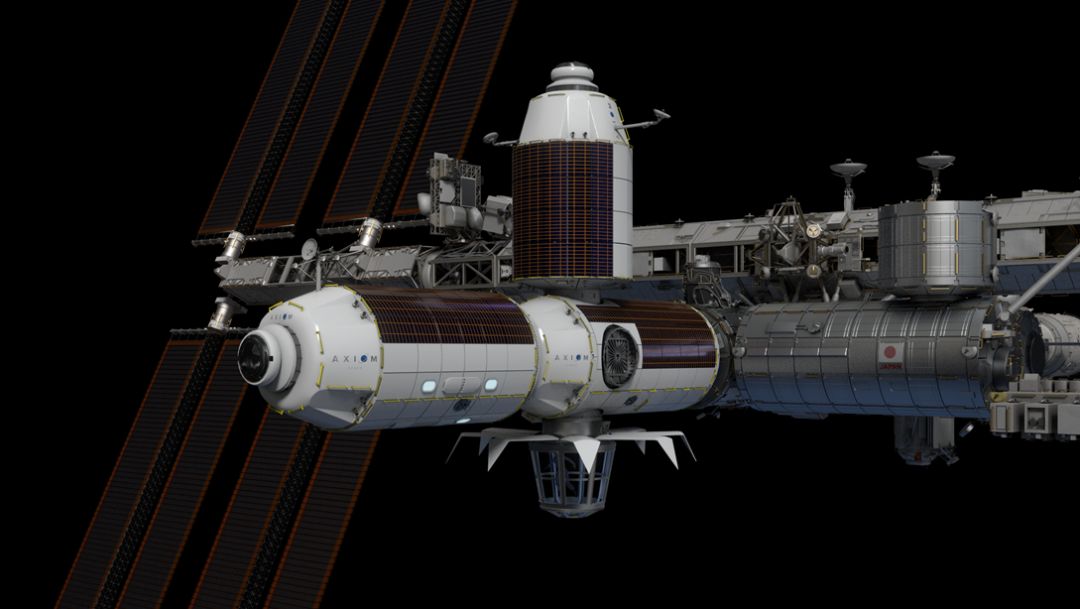

Axiom Space will start their station as an offshoot of the ISS, breaking off as more modules arrive (source; source)

Another space station builder is Axiom Space. Helmed by dozens of former ISS engineers and program managers, Axiom Space is planning to build a high-quality and accessible commercial space station, to be used for space tourism, filming, research and manufacturing, as well as national human spaceflight uses. They're currently bidding for an open docking port on the ISS to build off of, helping to ease the transition of the ISS from national to private, before budding off and becoming its own independent and free-flying station.

One critical addition is that they want to make space station "furniture" similar. Currently, everything in the ISS is custom-made and extremely expensive. Axiom Space wants to make it all "plug and play", using adapters and hookups that are standard on Earth, like you would furnish any office with store-bought desks, chairs and computers.

Axiom Space will then bud off and become an independent commercial station (source)

There remain many barriers to building the first private commercial space station. Launch costs are still high, private expertise is still limited and scattered, and the whole ecosystem is still very fragile. The components of a strong infrastructure are maneuvering into place, however, with cheaper launch providers (SpaceX, Blue Origin), affordable crew and cargo spacecraft (Dragon, Starliner), manufacturing tools (NanoRacks, Made In Space), and modules and space station "providers" (Bigelow, Axiom Space). I suspect the biggest obstacle right now is capital. It takes a lot to get it started. Economy of scale will take time, but it needs impetus to get moving, and time for the momentum to build. NASA can help the transition with support for a commercial takeover of the ISS, whose old age and eclectic construction will then fuel the desires for more customized and modernized accomodations. Once that "hump" is overcome, the boons of private, patented research and high-quality space-unique products will help finance the mass industrial move to space.

One of the biggest hurdles to private involvement in the ISS has been research law. All discoveries and inventions on the ISS are public property - nothing can be patented, so there's little incentive for tech companies to conduct wildly expensive R&D on the ISS without reaping the profits. While NASA is loosening those restrictions in recent times, it's still a public platform. This is important, because without an economic incentive for private companies to go to space, traffic volume will stay low and space travel will stay pricey. Six astronauts working full-time for two decades have discovered a lot, but not nearly as much as dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of private sector scientists and engineers working on many projects in competition with one another would be capable of.

However, many companies are looking to build private space stations and rent them out for others to use as they see fit, whether for researching new pharmaceuticals, food production or manufacturing techniques, or anything else that can be marketed. There are few examples of private research, for the above-mentioned reasons, with possible exceptions being product tests like the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module that proved the worth of Bigelow's whole product line. The BEAM is currently cleared to remain on the station until 2028, so it's basically a core module now. One example is Made in Space, which already tested its manufacturing technology on the ISS in early 2018, and plans to produce flawless ZBLAN optical fibers in space that are impossible to create on Earth.

Bigelow BEAM, the first private module on the ISS, proving the concept (source)

The other biggest hurdle to private industrial and research activities in orbit is the cost of launch vehicles. This barrier is rapidly being demolished by SpaceX and Rocket Lab, soon to be joined by Blue Origin and others. Spaceflight and space industry is becoming economically viable. Additionally, much of the infrastructure necessary for continuous industry in low Earth orbit is already in place. Thanks to the Commercial Resupply Services program, a whole series of private launchers and cargo spacecraft have been developed for the ISS that could easily service commercial space stations as well. As reusable spacecraft such as the SpaceX Dragon and Sierra Nevada Dream Chaser prove their worth and fly lots of missions, the costs will continue to come down, spurring more economic development in Earth orbit. Alongside this, NASA's Commercial Crew Development program has also developed the SpaceX Crew Dragon and Boeing Starliner, which while unable to service the upcoming Lunar Gateway, will be very capable of carrying passengers and workers to Earth-orbiting space stations. As both are reusable, their prices should also come down as they compete for paying passengers in a growing market.

Boeing Starliner and SpaceX Crew Dragon, both products of the Commercial Crew Program (source)

So, who's going to build the first private space stations? MirCorp, which temporarily took over the Mir space station in 1999, set a strange precedent. Mir was set to deorbit in anticipation of the International Space Station, but MirCorp offered to buy it and use it for commercial activities such as space tourism, the first orbital film studio, and private research. They even flew the first paying space tourist, Dennis Tito, and commissioned the first privately funded crew and resupply missions. However, NASA viewed it as a political threat to the ISS (other partners were thinking of backing out), and forced Russia to shut it down.

A few years later, Bigelow Aerospace was born, armed with the leftover patent of NASA's TransHab expandable space station module. They've been developing it for years with intent to build multiple space hotels and space labs, and boast far better performance than the hard cans that compose the ISS, and really every space station up to this point. As shown above, the BEAM on the ISS has proven these claims to be true. Perhaps the biggest thing holding back Bigelow has been both demand as well as launch costs, but both obstacles may be going away.

Bigelow Commercial Space Station aka Alpha Station, composed of two B330s (source)

The B330 is the main product Bigelow offers, being a 330 m³ expandable habitat that has more habitable volume than one third of the ISS at a fraction of the mass and complexity. These can be outfitted as habitats, labs, manufacturing facilities, storage, or anything else the customer dreams up, and allow them to entertain tourists, do research, or manufacture rare products to export back down to Earth. As you can see in the picture above, it could easily be served by Dragons or Starliners, which are just as technologically mature and ready to go as the B330 modules that have been developed over the last decade. Launch services for it are already contracted with ULA, and it's just waiting on a tenant to sign up.

Possible tenants include Made In Space and NanoRacks. Made In Space, as previously mentioned, has mature technology for producing high-quality optical fibers, and is currently developing the Archinaut, a revolutionary 3D printer that goes on the end of a robotic arm like the one that assembled the ISS. This has the potential to make massive objects in space, unlimited by the constraints of an assembly area like traditional 3D printers. They're also working on recycling old space station parts as more material for the Archinaut.

NanoRacks Ixion module, a spent upper stage refurbished as a space station module (source)

This ties in well with NanoRacks' ambitions to use spent upper stages as space station modules. This has been done before, with Skylab being a Saturn V third stage reworked into the first US space laboratory; but while Skylab was specifically designed for that purpose, NanoRacks wants to develop cutting tools to rework any spent upper stage into a usable hab. The big advantage is that its already built to withstand the vacuum of space, and it's much cheaper to launch into orbit - especially if it already delivered a satellite or station module. This has the added benefit of cutting down on space junk, and could be used to fuel the Archinaut. Together, NanoRacks and Made in Space are cutting down on the barriers to a space economy.

Axiom Space will start their station as an offshoot of the ISS, breaking off as more modules arrive (source; source)

Another space station builder is Axiom Space. Helmed by dozens of former ISS engineers and program managers, Axiom Space is planning to build a high-quality and accessible commercial space station, to be used for space tourism, filming, research and manufacturing, as well as national human spaceflight uses. They're currently bidding for an open docking port on the ISS to build off of, helping to ease the transition of the ISS from national to private, before budding off and becoming its own independent and free-flying station.

One critical addition is that they want to make space station "furniture" similar. Currently, everything in the ISS is custom-made and extremely expensive. Axiom Space wants to make it all "plug and play", using adapters and hookups that are standard on Earth, like you would furnish any office with store-bought desks, chairs and computers.

Axiom Space will then bud off and become an independent commercial station (source)

There remain many barriers to building the first private commercial space station. Launch costs are still high, private expertise is still limited and scattered, and the whole ecosystem is still very fragile. The components of a strong infrastructure are maneuvering into place, however, with cheaper launch providers (SpaceX, Blue Origin), affordable crew and cargo spacecraft (Dragon, Starliner), manufacturing tools (NanoRacks, Made In Space), and modules and space station "providers" (Bigelow, Axiom Space). I suspect the biggest obstacle right now is capital. It takes a lot to get it started. Economy of scale will take time, but it needs impetus to get moving, and time for the momentum to build. NASA can help the transition with support for a commercial takeover of the ISS, whose old age and eclectic construction will then fuel the desires for more customized and modernized accomodations. Once that "hump" is overcome, the boons of private, patented research and high-quality space-unique products will help finance the mass industrial move to space.

Comments

Post a Comment